by: Joshua Ogure August 5th, 2014 comments:

A Kibera Diary post by Map Kibera team leader, Joshua Ogure

Meeting With Teachers at Mchanganyiko Hall

In April 2014, my colleague Steve and I conducted a pre- project survey in Kibera, talking to parents, teachers and school heads. This was meant to find out the missing gaps on education information, and what their thoughts were on Map Kibera Trust, GroundTruth and other partners trying to make education information easily available, accessible and useful to everybody.

This was important to know before the actual project could kick off. Kibera people know exactly what they want, and no one can impose anything on them against their will. There is something that anybody who wants to do any project not only in Kibera but also other informal settlements must always observe: that you must involve the people, I mean the stakeholders at a really early stage. If you want your project to succeed, let it be a people-driven idea.

Meeting with Officials, School Leaders and Teachers

One of the Map Kibera founders, Mr. Mikel Maron, was travelling to Nairobi in June 2014, and there was a need for him to meet and engage with all the relevant stakeholders and authorities. I was to arrange and schedule for all these meetings, and so the planning began.

We began by meeting the Chief, the Assistant County Commissioner, and the Langata District Education Officer (DEO). The reason was to explain to them what our education project was all about, and what exactly we intended to do in the process and how it would be helpful to the community, as well as to seek for their support/approval/permission. This was also a sign of respect to them, by informing them prior about what was to happen in their localities. The approvals and interest shown by the authorities really gave us more courage and confidence to proceed with the project.

This was immediately followed by the stakeholder’s forum for School Heads and teachers, whose contacts we had gathered during the pre-survey interviews. We held our first meeting on June 6 inside the famous Mchanganyiko hall. Out of the 15 teachers and school heads we invited 10 of them turned up. The criteria to select the 15 was tricky, but all we wanted was to have at least every village of Kibera represented plus a few extra that had raised concerns during the pre-survey exercise.

According to the responsibilities delegated to the six Map Kibera team members that were present, Zack Wambua was at the door to take care of the registration, Douglas Namale was taking the notes, Maurine Owino was to introduce the project and present the website, Steve Banner was behind the camera to document the forum, I was to pick up from Maurine and lead the feedback session while Mikel was on standby to oversee and tackle any hard question that could arise from the audience.

As usual here, people arrived one hour late after the scheduled time. I could see my friend from Washington DC (Mikel) was not comfortable as he had another meeting to attend after this, but what could he do? This is Kibera, this is Nairobi, this is Kenya, and this is Africa, we’ve been meant to believe that lateness is a culture here. Do not ask me who said, because I don’t know.

Emerging Issues

So what were some of the concerns as far as the whole project was concerned?

School heads wanted Map Kibera to consider the governance capacity of schools to handle feedback, or have a team that will keep monitoring the sites. There was a general agreement that constructive feedback can help schools to run better but schools are sensitive, some information can lead to loss of students/teachers or cause closure, leaving schools vulnerable to troublesome individuals.

Teachers also argued that freely commenting on the school website can just lead to junk and that it needed some editorial — they thought schools should have the right to verify information. Some people could use the platform to tarnish a school’s name when for instance they have a personal grudge with the Director of that particular school.

“What are ways of addressing ethical issues on the site? What are the official channels?” one teacher asked. However, the information is out there anyway – in social media, word of mouth, etc. This platform gives an opportunity to address it. Though we all agreed that there was a need for investigation process on serious cases in order to remain factual.

Generally, teachers were positive about the online educational directory. They saw it as a big opportunity on awareness of what is happening at other schools, and they felt that typing on the site would enable them to market or advertise themselves or perhaps use the website to fundraise for their schools, and also for parents to make informed choices.

Teachers also emphasized that there was a need to have more information on the particular curriculum followed at each school, performance and test results, extracurricular activities, special needs programs offered, and the school governance structure.

“A good project, just a few adjustments here and there and we are good, it will help,” one teacher whispered to his colleague on their way out.

by: mikel July 22nd, 2014 comments:

We love data. Yet we often only know enough to use the data, without knowing the story behind it. But, while in Kenya to work on the Schools Mapping Project, I finally learned the story of a key data set to our project.

The creation story of a data set is essential for understanding the peculiarities of that data, and how data collection in the future can be improved (and there always will be a future data collection). Among the most popular and useful data sets released on OpenData Kenya are the locations and indicators of primary and secondary schools, Kenya wide. Over 70,000 schools which also double as polling places in elections. So, a super important and impressive data set.

And I have had a lot of questions about it. One of the key parts of our project is to make authoritative data and community data inter-operable. In the process of matching OpenStreetMap schools to Kenya Open Data (KOD) schools, I found something puzzling. The locations in KOD of schools in the Kibera slum were off by hundreds of meters from the OSM data, and not in a consistent way that would suggest a projection issue or such. We have reason to trust the OSM data, as it was collected directly by GPS and confirmed with the community (and, it’s one of the powers of OpenStreetMap that our data story is completely out in the open). Other studies of the KOD data set had also found issues; like research from the World Bank (Points of Knowledge – Crowdsourcing Solutions to Improve Data Accuracy and Re-use in Kenya), which found a majority of primary schools were mis-located. Yet, this was a stupendous data set to put together, a real challenge, over 70,000 schools, back in 2007. How did they do it, and what can we learn?

Last month, I found myself sitting across from Teddy Ochieng at the Gigiri Java House. Through colleagues at USAID Geocenter, I connected with Teddy, currently a GIS officer at USAID. Teddy was generous with his insights on the state of school GIS data. And he just happened to have been a part of the team that collected the 2007 schools data. A man behind the curtain moment!

The Ministry of Education provided a list of over 70000 schools. They started with 15 teams, ending with 10. Each team had 3 people: a lead data collector, an assistant, and a driver. Most all of the data was collected in 2007, but some areas affected by the 2007-8 post-election were hard to reach, and waited until into 2008. They used ArcGIS and Excel to manage data. GPS used were professional end models from Trimble and Magellan, with our old friends the with Garmin eTrex for backup, and manually read and re-digitized the collected latitude / longitude into the database. Data analysis was undertaken in 2010.

Nairobi and other urban areas were particularly challenging. Especially slums — slums are dense, and its sometimes hard to get a signal. The teams had a lot of data to collect, and were in a hurry. To reach many slum schools, you must walk. It’s hard to access by vehicle, often impossible, and it can be uncomfortable and difficult (or even dangerous) for outsiders to roam. This is just conjecture by me, but in searching for a reason, perhaps sometimes the team did not get out of the vehicles. Manual re-entry can also introduce errors. In any case, it seems some factor conspired to introduce some inaccuracies into the schools, especially within informal settlements.

The objective of the project was to go further, and essentially, to set up the Ministry of Education to manage this data better in the future. There are numerous departments like the Information Management Office, and Planning & Quality Assurance, and systems even within the Ministry of Education which don’t keep consistent and linked databases. One key thing they did was assign every primary and secondary school a unique identifier to help with this. Curiously, only the secondary school identifiers made it into OpenDataKE. Ultimately, the hope was to merge all education databases, including the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) which keeps information on teachers, and Kenya National Examinations Council (KNEC). There is even apparently a photo database of each school within the MoE.

I was left with the impression that the challenges in the work Map Kibera has taken on — to link and update school databases in one place — are real ones the Ministry of Education has itself grappled with at a much larger scale. And, I  appreciate much more the impressive challenge of collecting such data for an entire country. This data story reveals an opportunity … if we can find a way for our Open approach to grow, perhaps to county level, then there’s a real repeatable method for keeping school data linked, accurate and up to date. We can take advantage of new networked data collection methods, distributing the cost of data collection to manageable places and to schools themselves.

by: mikel July 16th, 2014 comments:

The two weeks I spent in Kenya in June were probably the most productive and open to possibility since the often referenced 3 weeks of mapping in Kibera back in 2009.

My goal was to lend my weight to the push off of the education mapping project in Kibera. In short, we got our act together to a tight, professional level, and drew into the process people and organizations from all levels. In four parts, the mappers and the media team developed the work plan and logistics for data collection. We organized two groups of community advisors to help guide the project and the website. We informed and gathered support from local government. And I connected with government, NGOs, the tech community, and international development organizations looking at the topics of education & data. And I helped deal with the inevitable daily minor crises that are part of the territory of working in the slums.

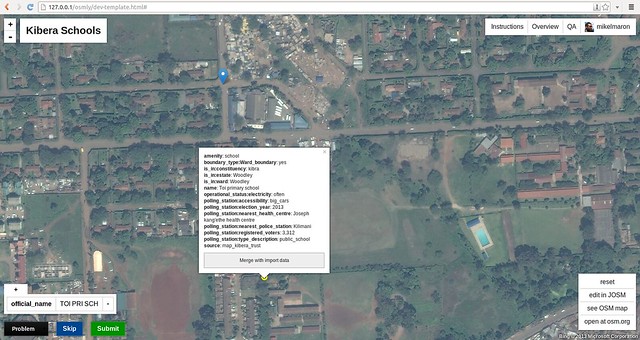

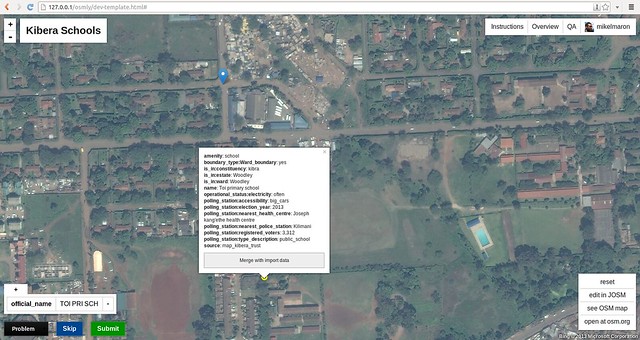

The Kibera team for this project is a focused group of 3 mappers, Zack Wambua, Douglas Namale, and Lucy Fondo; and 3 media guys, Joshua Ogure, Steve Banner, and Jacob Ouma; as well as Yvonne Tiany scoping feasibility in Mathare. We examined the landscape, estimated the work involved in recollecting approximately 250 schools, and geographically divided up the work into three teams. We hashed out the specifics of two dozen data fields for collection, got feedback from our advisory group, settled on the collection form, and preset labels in the map editor for those data fields. There were timelines, contracts to sign, facilities to arrange (Kibera office and iHub), and we started a weekly coordination call on Fridays. The was all easy with our experienced crew.

We were eager to check that we were on track with parents and school heads. We held two focus groups, one with school leaders (at our frequent host Mchanganyiko)Â and one with parents. Most of these folks had already been introduced to, and interviewed for, the project by Joshua, so we could quickly get into details with the presentation and hands on demo of the Open Schools website that we are building. GroundTruth and Development Gateway have been working hard on the basic beta website structure, but had lots of questions on real usage. The energy levels cranked up when they got to use the website itself, real excitement. I hovered and wrote pages of user observations. This led into a very productive dialogue about the project as a whole.

For local government officials, we drafted a formal letter informing on the crucial details of the project, and requesting their support. Happily, the reputation of Map Kibera helped us to secure meetings with these busy individuals, they all gave us signed & stamped support, and expressed genuine interest in the outcomes of the work. It’s important that the administrators and representatives are informed and consulted early in the project. Their support helps assure schools that we are managing the information collected responsibly. We sincerely hope the data will be of use to the Honourable Member of Parliament for Kibra, the Assistant County Commissioner, the County Education Director, the District Education Officer, and the Chief of Saran’gombe.

In my “spare” time, I managed to meet with representatives from various NGOs and international organizations. Fascinating chat with USAID about previous schools mapping. Sharad Sapra from Unicef set some lofty goals for our work (think continent sized). It was great to connect with Concern Worldwid, who are already using our data, and have data on informal schools we can use. Had a whirlwind discussion with Innovations for Poverty Action about half a dozen points of connection. Interesting to check out the operation and insights of Bridge Schools. Promising discussion of mapping with Peace Corps Kenya. Open Institute was generous as ever with their efforts, especially looking at the role of devolution. Had a last minute dinner with Ashoka education innovators. And on top of these, great catching up with friends and exploring everything with Erik Hersman, Matt Berg, Sasha Kinney, and Mark de Blois.

We have lots more to expand on with all these threads. Thanks to everyone for a fulfilling and promising trip. I came away convinced that our approach is needed and our focus on education is timely, and that this project will be of service to improve understanding of education in Kenya.