Way back in December, Map Kibera hosted a panel discussion at the ICTD annual conference in London. We held a session on citizen mapping and media, and invited panelists from a variety of video, mapping, and other grassroots digital projects. Of course, the most enthusiastic panelists were Zach Wambua and Douglas Namale, mappers and scholarship recipients from Kibera.

After an initial denial of Zach’s visa by the British consulate, we were assisted in finally getting both Kenyans admitted. In the end, we think the event was well received we managed to cover a lot of subject matter in a very short time. Douglas and Zach answered most of the audience questions, and had the chance to talk about their community and the issues they faced during the project. They were very well received, as evidenced by the fact that practically the only time we saw them throughout the week was when they shot us exhuberent glances as they talked excitedly with new friends from around the world. Clearly, the scholarship was worth all the trouble Tim Unwin and others put into it.

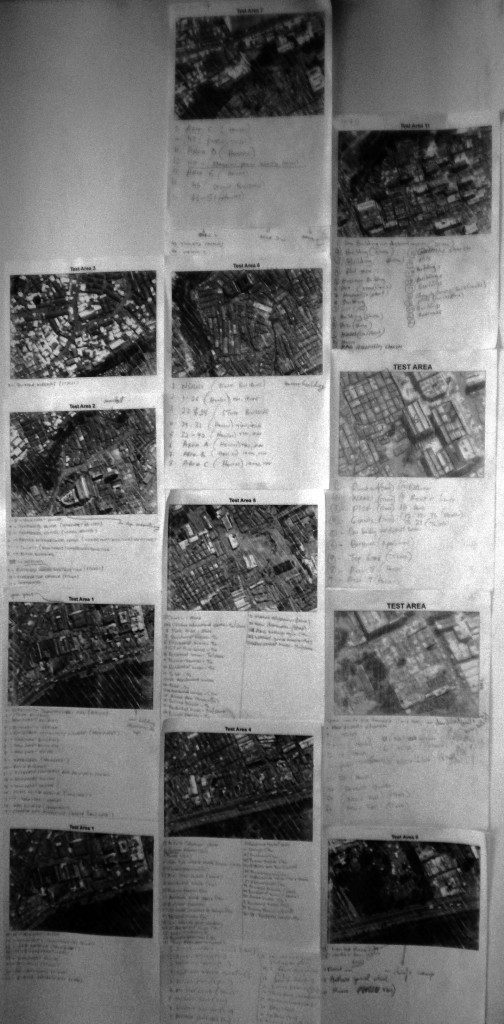

We also had Raed Yacoub from Voices Beyond Walls present about their wonderful work in video and mapping with kids in Palestine, and had a lot to share with him about community driven work.

Other panelists we invited couldn’t attend, however, due to the high cost of the conference even just to present at a single panel – they couldn’t afford the fee and neither could we. I was pretty upset about that. This might belie the fact that I’d never attended a proper academic conference before – I’m more experienced with unconferences and the like. In fact, the most interesting part of the conference for me was the contrast (and debates) between academic and practitioner.

The opening session of the conference included a “practitioner panel” with celebs like Erik Hersman from Ushahidi and Ken Banks of Frontline SMS. The message they sent was loud and clear – academics should make a practical impact.

Some sample Tweets during their talk:

“It’s often people who aren’t “qualified” doing experimentation that leads to the best innovation”

“Re: academic – practitioners divide. It’s possible to build methodological bridges. Everyone is a knowledge constructor. Herehere!”

“Ken banks: it’s totally wrong to fly tech implementations around the world – trust local people to work out own implementation”

“We shouldn’t be surprised that tech innovation is coming from Africa says Eric”

“ICT4D research needs to be communicated in language that pracitioners can more readily appreciate”

“I disagree w/those on panel who suggest academics can’t/aren’t doing “real” work in the field, or vice versa”

Browsing the poster sessions and attending many of the paper presentations, I was often struck by the murky in-between area in this particular discipline – many academics were implementing projects, to some extent, while practitioners like ourselves are engaged in research at the same time. And yet, there was a clear difference in purpose and culture. This is still very much an academic field in the making, and many attendees I spoke to were somewhat confused what the outlines were. Were we there to hear companies pitch ideas? Microsoft had funded a huge amount of the featured research. Were we looking for new cool products like a trade fair? There were a number of those on hand, too. Were we discussing thorny issues of international development? Not nearly enough of that for my taste. Were we talking about how technology operates in the world, internet policy, mobile phone usage? This last them came up in many of the papers. But for me, a lot of the discussion left out the primary issues of benefit to the poor and marginalized in favor of interesting graphics and analysis without much follow up.

Although there was a lot of talk in the Tweetosphere about the need to make this more of a Southern conversation, and many attendees were in fact scholarship recipients from the developing world, this perspective seemed sorely lacking from the main events of the conference, even though as Erik and Ken pointed out, a lot of innovation is now coming directly out of the global South etc. There was also a lot of disappointment in the room when Atlanta, GA, USA was announced as host to the next conference because it would mean even more visa troubles getting foreign, poor participants in. This is clearly because it’s academia we’re talking about – and there are still major barriers to most of the world attending – or creating – the kind of elite institution that produce papers accepted for publication. But aren’t we talking about a field that is critically happening NOW in those poorer countries? Do wealthy white people really need to keep talking to each other about it? (Of course – no easy answers here to inclusion problems that plague the development field worldwide).

I was painfully reminded of the frequent divide between benefiting researchers’ thirst for knowledge and benefiting the poor when one researcher presented on mobile phone use in Rwanda. He had acquired amazing amounts of phone data from the dominant phone companies, and mapped out the call patterns showing (predictably, but still kinda cool to see) the rise in calls in a particular region during outbreaks of civil unrest. He had then conducted a study by surveying the people individually in a sample study, because he still didn’t know who was calling who – some privacy did remain. Now, fine, but a comment he made really bothered me: no one EVER refused to answer his questions. His take: “Now I would NEVER answer some of these personal questions on my income, and who was the last person I called and why! But these friendly Rwandans always replied!” The person sitting next to me and I exchanged glances – was this supposed to be a good thing? WHY did every Rwandan reply with personal information to a stranger calling their phone? WHY is it so easy to do extractive research in most developing country settings? Could there be an ethical issue at stake? Has anyone bothered to consider the politics or social issues behind surveying people who are rather at a power disadvantage to you, without offering anything in exchange? And what exactly was the research supposed to lead to – what was its practical purpose – to lead to more publications and better careers for foreigners? Maybe there was more to it, but this wasn’t discussed during the presentation. Perhaps this begs the somewhat existential question, does knowledge for knowledge’s sake make sense when we’re talking about the poor and disadvantaged?

I’ve thought a lot about this during our work in Kibera, a hotbed of academic research. Most people we would meet walking around would ask, are you a student or a researcher (the 2 options)? I would say that optimistically, at least 50% of the time the research does not make it back to the people, much less have an impact on their lives in the long run. Even just enlightening the general public as to research outcomes would be something. It’s much like when documentary filmmakers (like the ones who made Good Fortune) film in Kibera and then produce movies about critical local issues that can’t even be viewed legally online in Kenya.

Having said that – there is clearly a lot of desire among conference participants to bridge the gap between these rather artificially separate disciplines. I hope that this moves forward between now and ICTD 2012.

This post is part of a series exploring the ideas and issues that have emerged in our research project with Institute of Development Studies, supported by DFID. All posts from the Map Kibera team, the researchers from IDS, our trainers and colleagues are collected here. As always, we are eager to discuss this work, so we hope to hear your comments.